We are all natural storytellers. In a world cluttered with facts, events and people, we use narrative to bring order to the chaos, helping us carve a path forward and forge ahead. While facts can be overwhelming, stories feel satisfying and empowering.

In more mechanical terms, stories are causal relationships that help us organize information and digest it. As a consequence, we are able to gain insight and learn. Given the appropriate context, these conclusions can often feel like innate truths, eliciting an emotional response, which appeals to our emotional brains.

Looking at the marketing sphere, Seth Godin has expounded the importance of marketers thinking of themselves as storytellers, facilitating these causal relationships between people, events and products in order to resonate with consumers.

However, his appeal is somewhat less than timely, as marketers have not only understood the importance of storytelling for some time, but have mastered it. In fact, marketers have learned to harness the psychology behind our tendency for story, exploiting the narrative fallacy to create powerful advertising.

But what is the narrative fallacy? The narrative fallacy is a psychological concept that refers to our tendency to weave narratives and causal relationships between events, often to a fault.

Advertising often conjures up stories around products. These stories feature characters in fictionalized narratives using products and consequently, enriching their lives. This is a rather simple, brute force approach of demonstrating benefit in order to sell the product.

Other times, ads opt to be less direct, aiming to generate an overall positive affect with a story and displace it onto the brand. In essence, a loosely related, but resonant, narrative serves to create a sort of “halo effect” for the product. This effect is due to the narrative fallacy concocting a causal relationship between the product and the ad. Even if the product and storyline are seemingly discordant, our minds stretch their imagination to weave a plausible narrative.

Some brands look to be less direct still, electing to be highly suggestive with their advertising. They don’t construct any sort of narrative, but simply provide the ingredients for one.

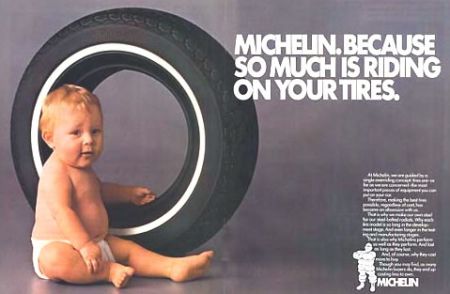

The above Michelin ad merely features a child, a tire and a provocative statement, but despite the simplicity, it is surprisingly powerful and effective. Rather than telling a horrific story to the audience, it suggests one. With all the ingredients present, the narrative fallacy takes over to fill the plot holes with dramatic and highly personal details. This makes the ad resonate. Suddenly, all your personal experience floods in to generate an emotional response. In a sense, you are as responsible for the ad’s effectiveness as the advertiser who created it.

In all, this refutes the notion that marketers merely tell stories. Good marketing succeeds because it exploits the narrative fallacy – providing a compelling framework that resonates and enables us to fill in our personal details. In a way, we brew our own stew, with marketers setting the table with the right ingredients. These narratives resonate because our own personal experiences populate them, creating powerful, personalized stories that facilitate an emotional connection to the brand.